The incandescent lamp was the killer application of electrification. Just a couple of years ago it was decided to say goodbye to this lighting workhorse. An initially assumed successor – the Compact Fluorescent Lamp or CFL – was not embraced by consumers. Nevertheless, it pioneered the transition to energy-efficient lighting. The LED lamp takes advantage of this groundwork and now takes over the lead.

This article is the fourth in a series of four on product evolution. They illustrate how technological evolution can explain ‘the origin of products’. Obviously, this type of evolution is different from what we are used to with biological species.

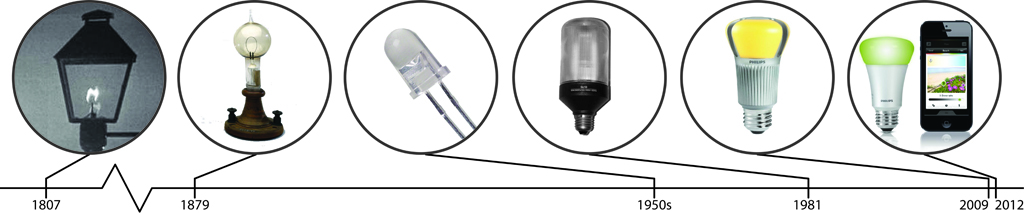

For thousands of years people used oil lamps and candles to illuminate their homes during the hours of darkness. Neither produced much light and both were inconvenient in use as their fuel needed to be regularly replenished. Besides that, open fire is notoriously dangerous. Then, at the start of the 19th century, gas lamps fuelled by coal-gas distributed by a network of pipes turned out to be an innovative solution for the problem of illuminating the streets of European cities. Gas lamps became a huge success, but also continued to be dangerous because of their open fire and toxic fumes. Numerous theatres illuminated by gas lamp burned down, killing many. The world longed for a safer type of light!

Gas lamps became a huge success, but also continued to be dangerous because of their open fire and toxic fumes

Electric light

Progress sometimes comes about as a result of bizarre experiments. That was surely the case with the Italian, Luigi Galvani, who once touched the leg of a dismembered dead frog with a metal object. The frog leg kicked as if alive. This drew people’s attention to the phenomenon of electricity. Alessandro Volta, also Italian, continued experiments in the hope of understanding the phenomenon and developed the first ever battery. This provided the first practical source of electricity, which was then used by David Humphrey for more electrifying experiments. He took huge numbers of batteries and a platinum strip and passed an electric current through it until it illuminated light. And there it was, electric light by incandescence! A second experiment that produced light used an arc between two carbon rods. The electric arc made it to a first commercialised version of electric light, known as the arc lamp. However, it was not ideal. The lamp produced an intense light that could not be dimmed. What is more, it still produced unpleasant fumes and the rods needed to be replaced regularly.

No fewer than 19 inventors claimed patents on incandescent lamps before Swan and Edison

Incandescent

Decades of pioneering experiments finally delivered incandescent lamps. In 1879 two different inventors on both sides of the North Atlantic claimed a patent for a first incandescent lamp using thin carbon wires that lit up and glowed when sufficient electricity was conducted through them. The inventors in question were Joseph Swan in the UK and Thomas Alva Edison in the USA. They were by no means the first to experiment with these lamps. No fewer than 19 inventors claimed patents on incandescent lamps before Swan and Edison. However, all these pioneering predecessors failed to commercialise their inventions.

The incandescent lamp was the first large-scale application of electricity. Obviously this requires power stations to generate and networks to distribute the electricity. In the early days, dual current (DC) dominated and only short distances could be covered between the power station and point of use. At that point in time there was not yet any voltage standard in networks. It was only when networks started using alternating current (AC) that they could cover larger distances and the need arose to use same voltages in coupled AC networks. From that point on the world became divided into 110 Volt and 220 Volt networks, something that has not changed since.

The incandescent lamp was the first large-scale application of electricity

The incandescent lamp was a huge success. The first types with carbon filaments could only be used for about 40 hours. This meant that lamps had to be replaced quite often soon. As a result a major industry arose for the production of incandescent lamps. These new industrial companies started to employ inventors that experimented with all kinds of materials and constructions with the aim being to increase the lamp’s life. Once it had become clear how tungsten could be processed into ductile filaments, the lifespan of the incandescent lamp improved to approximately a thousand hours. However it still had to be regularly replaced, usually once a year, and the screw base interface was therefore designed and became a standard we still use today. The lamp that evolved in this way became known as the general lighting solution or GLS and continued to be the preferred type of electric light for consumers for almost a century.

The lamp that evolved became known as the general lighting solution or GLS

Gas discharge

Inventors in the mid 19th century discovered that light could be produced by making gas discharge into a glass tube. The process resembles the flash produced by lightning but than on a much smaller scale and in a contained and non-dangerous form. Again, decades of experimenting and some primitive applications were necessary before the elements needed for what became known as the tube lamp (TL) were ready in the early 1930s. Then World War II started and the greater illumination provided by the TLs was welcomed by the wartime manufacturing industry. The volume of TLs used quickly went up. Consumers in Europe and North America, who were used to the warm light of the GLS incandescent lamps, were not keen on lots of cold TL light in their houses. However, in regions where consumers had not yet grown used to incandescent light, the reception was much more positive and TLs swiftly became widely used.

Environmentalism’s rise

Looming disaster proclaimed in ‘The limits to growth’, which was published in 1972 by a think tank named the Club of Rome, kick-started environmentalism. It changed the perspective of many towards the viability of the earth and the availability of natural resources. A year later the first oil crisis also demonstrated how access to oil could suddenly became a problem and people started to realise that it would be beneficial if we could reduce our energy consumption. As a result of these changing circumstances governments started stimulating research into more efficient types of lighting.

The changed perspective towards the viability of the earth and the availability of natural resources prompted governments to stimulate research into more efficient types of lighting

Then, once again, in the same year (1976) and on both sides of the Atlantic, a new type of electric lamp was patented. This time it was the Compact Fluorescent Lamps or CFL. Laboratories of both Philips based in the Netherlands and GE in the United States developed a more conveniently shaped version of the TL with the screw base so that it could be used in the same sockets that, until then, had only accommodated GLS incandescent lamps. Initially only Philips commercialised the lamp that was introduced to the market in 1981. This first CFL weighed over half a kilogram and was so bulky it did not fit into many lampshades. Besides its pale light, it also flickered annoyingly during the three minutes it took to heat up and it was expensive. So it was no surprise that people did not really embrace this new lamp. Thanks to lots of development and the ever-shrinking size of electrical components a second generation CFLs was introduced in the 1990s. This second generation became more efficient, more compact and eradicated the flickering. However, it took a second wave of environmentalism for CFLs to become more popular. This time the root cause was global warming induced by greenhouse gases that was discussed in the 1997 Kyoto protocol. Now governments were urged to take measures to reduce energy consumption to avert climate change. The much improved second generation CFLs had become a viable alternative to the GLS incandescent lamps and policymakers recognised the opportunity presented by this energy-efficient alternative. In short, this led to the banning and phasing out of the GLS incandescent lamp over a decade later. In the meantime an even better alternative became available.

CFLs had become a viable alternative to the GLS incandescent lamps as a measure to reduce energy consumption to avert climate change

Solid state

The semiconductor industry that emerged at the end of the 1950s gave us more than computer chips. The technology that provides microscopic magic on silicon wafers is also used to make what is called Light Emitting Diodes or LEDs. Officially the family of lighting technology of which the LED is part is called Solid State Lighting (SSL). The first well-known applications of LEDs were the tiny red indicators used on many electronic devices and the LED matrix displays on early desktop calculators. As is common in many fields of technology, initial applications are confined to a narrow set of not so demanding applications. Then, over time, development efforts by armies of scientists and engineers produce much-improved versions of the young technology, allowing it to spread to more demanding applications. The same happened to LED.

When legislators drafted their plans to phase out the GLS incandescent lamp, they could not yet bank on the availability of the LED lamp. Hence, legislation trusted that the CFL could do the job. However, by the time the GLS incandescent phase-out legislation came into force between 2007 and 2012, the LED bulb had already entered the stage.

When legislators drafted their plans to phase out the GLS incandescent lamp, they could not yet bank on the availability of the LED lamp

Philips first introduced a 60W incandescent GLS equivalent LED bulb in 2009, to replace the old workhorse. At that time the LED bulb was still much more expensive than the CFL, but prices quickly eroded. The first LED bulbs on the market only produced a single light colour and were operated in the same way as traditional GLS incandescent lamps using on-off switches. Only a few years later, in 2012, Philips again introduced an amazing novelty, namely LED lamps that could produce millions of colours, change intensity and were ‘connected’ to the Internet of Things (IoT).

These new lamps can be controlled wirelessly using a smartphone, even if the user is a long way from home. What is more, apps can be programmed to change light intensity or colour in many conditions, thereby expanding the number of possible uses. The incandescent lamp was the killer application of the electrification and now its final successor was set to become the first large-scale IoT application.

Future outlook

It looks like the LED lamp is the future. Sockets left empty by incandescent lamps skip the CFL and are filled by LED bulbs. Illuminating large surfaces was once the domain of TLs. Now an LED-based alternative is being marketed for TL sockets as well.

The retrofit LED lamp seems to be much better positioned than the CFL to meet consumer desires and needs

The CFL was not very in tune with consumer tastes and, therefore, it could not oust the GLS incandescent lamp on its own merits. The retrofit LED lamp seems to be much better positioned to meet consumer desires and needs. How lamps will evolve in future will remain the topic of debate for some time to come. However, the retrofit use of screw based socket LED bulbs might not last forever. After all, what use is a screw base socket if the lamps are replaced 20 to 50 times less than was common for GLS incandescent lamps?

Conclusion

The LED lamp was made possible by advances in technology that provided LEDs and microelectronics. The available infrastructure of screw base sockets combined with the imminent phase out of the GLS incandescent lamps then provided the conditions for the LED lamp to emerge.

The evolution of products like the LED lamp cannot be understood if described in technological terms only

The evolution of products like the LED lamp cannot be understood if described in technological terms only. A more comprehensive picture is provided by a description of the factors that influence the emergence and subsequent evolution of these products. In this case societal change created awareness amongst the general public that behavioural changes were needed to avert climate disaster. Policymakers provided legislation that enforced the phase-out of the GLS incandescent lamp, to the benefit of more energy-efficient alternatives. All in all these contextual factors appear to be part and parcel of the evolution of the LED lamp.

Copyright © 2018 Huub Ehlhardt. All Rights Reserved. Please contact us for re-use of this article.

The book ‘On the Origin of Products’ is available via Cambridge University Press, Bol.com and Amazon. This site also provides an introduction to this title.

Thanks to the excellent guide

Whether the LED will make a significant contribution to reducing climate change is not yet known. Given the much lower energy consumption, the response of consumers and users has so far been to buy far more lamps and leave them switched on for much longer: the standard response to increases in efficiency of any device.

Indeed. This is valid remark. In scientific literature this is called the rebound effect. More information on this phenomenon can be found on Wikipedia or this scientific paper ‘Technological progress and sustainable development: what about the rebound effect?‘.

Interessant artikel. Compliment,