Can product development be considered an evolutionary process? Until the late 1980s product development was generally considered to be a ‘linear’ process. The common idea is that the development of products is entirely controlled by inventors and engineers. ‘On the Origin of Products’ by Arthur O. Eger and Huub Ehlhardt aims to show that products are not simply invented from scratch. In the book the authors, who both have a background in product development, explain why the emergence of new types of products can be regarded as an evolutionary process. For people who are interested in the subject they have written a series of short articles about the origins and evolutionary development of four products. Without going into detailed theory these articles provide the reader with an overview of the origins of the word processor, the e-bike, the smartphone and the LED lamp.

The evolution of products over the course of many decades clearly does not follow a predetermined long-term plan

Although everybody will agree that each individual product is intentionally developed, these articles will show that, once we consider the evolution of these products over the course of many decades, it is clear that they do not follow a predetermined long-term plan. This article is an introduction to the series of four and explains briefly why the authors consider the development of products to be an evolutionary process.

Traditional view on innovation and product development

Innovation has become a buzzword and seems to be regarded as an economic elixir. It is generally associated with the invention, development and exploration of products or services that provide new or improved versions of existing things. Development is always one of the processes required to bring innovation to the market.

Until the late nineteen eighties product development was generally considered to be a ‘linear’ process. Successful new (versions of) products were considered to be the ‘next logical step’ in the continuous improvement of the product with regard to the price and performance. The basic thought behind this idea was the – in practice non-existent – principle of perfect competition, a term derived from economic theory. According to this theory a product can only survive in a market if it has an improved performance and/or a better price compared to its predecessors.

Phenomena, such as ‘path dependency’, ‘technological lock-in’ and ‘dominant design’ cannot be explained by the linear model

Evolutionary Models

In the last quarter of the 20th century this principle was widely criticised: development processes (e.g. product development) seemed to be much less predictable and unambiguous than the linear progress model suggested. Research was initiated in different fields of interest in which innovation processes can be studied, such as economics and technology studies, to find new explanatory models to explain the complicated way that innovation progresses. It is striking that this research, which has very different points of view due to the many research backgrounds, has always ended with the same kind of explanation, namely evolutionary models. However, the practical consequences of this point of view remained unnoticed for decades. The linear model continued to be the generally accepted theory in studies of product development and innovation management. Despite this, the practical implications are far-reaching: a number of economic phenomena, such as ‘path dependency’, ‘technological lock-in’ and ‘dominant design’ cannot be explained by the linear model and are therefore considered to be ‘anomalies’. Nevertheless they can be explained when an evolutionary product development model is used as a framework. This was a key reason to continue investigating the possibilities of an evolutionary vision of product development and innovation.

Most of the products that are developed are nothing more than slight adaptations or improvements of earlier versions of the same product

History matters

Most of the products that are developed and brought to the market are nothing more than slight adaptations or improvements of earlier versions of the same product. Even when, once in a while, a completely new type of product appears, it adds some novelty but always builds on existing knowledge. The wheel is not reinvented, but refined and used for new purposes. Besides that the freedom to design newer versions is narrowed down by earlier technologies, standards or products. The development path travelled so far cannot, as it were, be completely redone. This significantly limits the amount of freedom to design newer versions. In short, history matters.

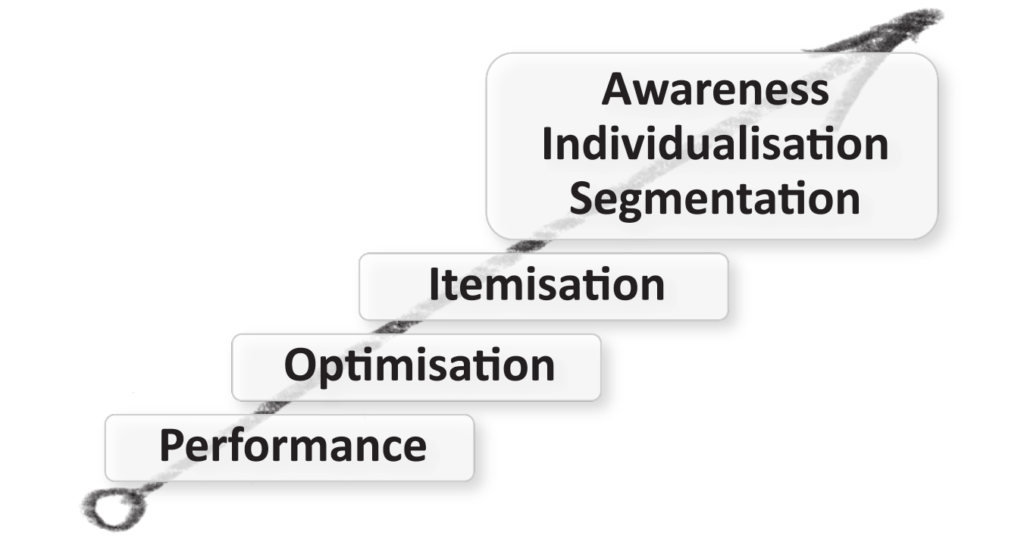

Product Phases

An important first step was made in the study by Eger who, starting out from the well-known six phases of the economic product life cycle (development, introduction, growth, maturity, saturation, and decline (or ossification)), combines these phases with a qualitative model of six product phases (performance, optimisation, itemisation, segmentation, individualisation and awareness). The most important conclusion of this study is that the focus of the product development activities is influenced by the place the product has in its life cycle. A practical implication is that designers need to take explicit account of this relationship when choosing specific product development activities. Besides that the chance the product development process will deliver a successful product can be enhanced when consideration is given to the life cycle.

In order to increase the chances of success, product development should take the product phase into account

In the early phases of a new type of products’ existence, the attention of the designer will focus mainly on functional aspects: first on technical functioning and later on the improvement of quality, ergonomics and safety. Next, the designing activities focus on price, styling, extra features and offering a line of products. However, in the later phases of a product’s existence, there is a shift in emphasis. The development of extra features and accessories is an ending process: at a certain moment, the performance delivered exceeds what is needed. As a product progresses into later life phases, the importance of the experience provided by the product increases and so-called ‘emotional benefits’ are added to the product.

Despite it being made up of man-made elements, the ecosystem is part and parcel of the evolution of products

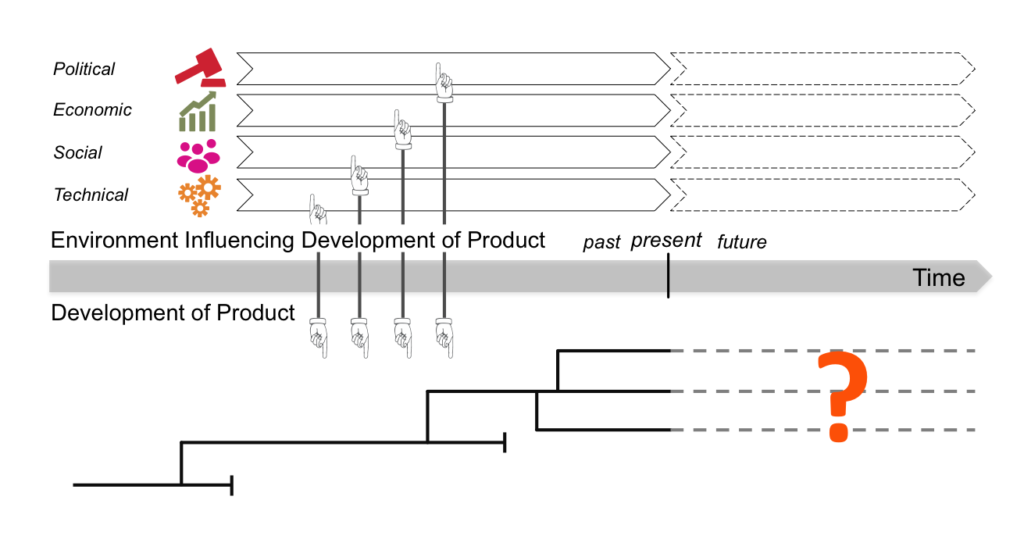

Ecosystem

Ehlhardt studied the same subject, but started out from a different perspective: how do new types of products emerge and what influences their subsequent development? In the case of biological species, it is widely known that the ecosystem in which they live and reproduce plays a crucial role in their evolution. Changes in climate may, for example, lead to the extinction of one species while causing another species to thrive. In the case of products it has been demonstrated that, despite it being made up of man-made elements, their ecosystem is part and parcel of their evolution. One of the cases explored, the LED lamp, shows how developments in our environment have led to changes in attitude towards energy consumption and climate change. The Kyoto Protocol, in which countries agreed on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, eventually led to legislation to phase out the inefficient incandescent lamps. This treaty boosted sales of alternatives such as the CFL and a few years later the LED lamp. If the treaty had not been signed, energy-efficient lighting systems would, at the very least, have emerged much more slowly. Indeed, they might even have developed in a completely different way.

Ehlhardt (2013) proposed the Product Evolution Diagram as a means of providing a framework for analysing the development history of products. This framework includes an ‘ecosystem’ as a means to provide a systematic mapping of factors from the environment that influence the development of the product. A detailed explanation of this diagram can be found in ‘On the Origin of Products’ (Eger & Ehlhardt, 2017).

A process of descent with modification provides an explanation for the origin of products

Conclusion

New types of products are not just invented from scratch but are developed on top of what has been invented before. Their evolution is fed by technologies developed for other purposes and is, to a large extent, determined by the way people deal with these products. The origin of these products can be explained by a process of descent with modification but then, of course, in a way that is different to what we are familiar with in nature. Although it is not yet commonplace for designers to think about evolutionary next versions when designing products, tools are now being provided for this purpose.

References

- Eger, A. O. (2007). Evolutionaire productontwikkeling. Den Haag: LEMMA

- Eger, A. O., and Ehlhardt, H. (2017). On the Origin of Products. Cambridge University Press.

- Ehlhardt, H. (2013). Product evolution diagram; a systematic approach used in evolutionary product development. In DS 76: Proceedings of E&PDE 2013, the 15th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Dublin, Ireland, 05-06.09. 2013.

Copyright © 2018 Huub Ehlhardt and Arthur O. Eger. All Rights Reserved. Please contact us for re-use of this article.

The book ‘On the Origin of Products’ is available via Cambridge University Press, Bol.com and Amazon.